Case Study Report on Youth Subculture: Punk

Lisa Ainsley: BSc (Hons) Sociology

Introduction

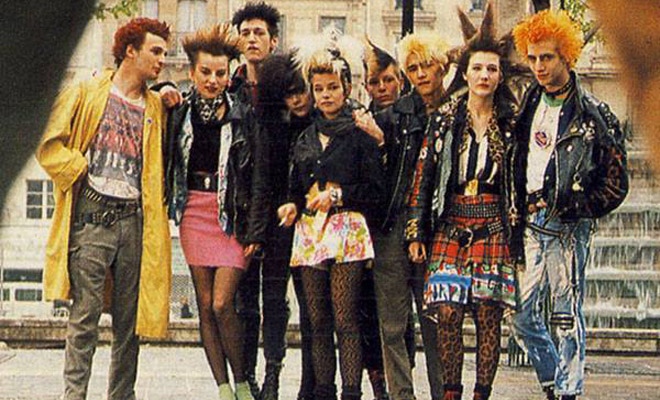

This case study will examine the youth subculture of punks and punk rockers. The term ‘subculture’ will be defined and academic studies on punk rockers will be discussed. The factors that have influenced the subculture such as class and gender, the cultural symbols of the subculture and their portrayal in the media will also be discussed. The reason this subculture was chosen is that the punk subculture has been around for some time and the style is quite unique.According to Mason (2008), punk subcultures have developed since the 1960’s and began in the roots of hairstyle. O’Connor (2004:410) notes that punk subculture has “the emphasis on individual self expression and the extravagant dressing up”. While punk rock music can make powerful statements, appearance is important in the rock genre. Subculture according to Hebdige (1979:2) is “the expressive forms and rituals of those subordinate groups”. This means that subcultures have practices and norms that do not fit with wider cultures, as their culture is subordinate to dominant culture. According to Merton (1938:675) this is a process of “deinstitutionalisation, of the means is one which characterises many groups in which the two phases of the social structure are not highly integrated”. This means that dominant culture norms of wider society are not fully taken on board by the norms of Subcultural groups.

Literature on Punk Subculture

Bešić and Kerr (2009:114) argue that “interests, social skills and talents are probably largely responsible for many peer crowd organisations”. However to be identified as a Punk or a Goth they are unlikely to be identified as such without the distinctive outward appearance (Bešić and Kerr, 2009). This relates to what Hall (1997) argues that signs and signifiers of a subculture constructs that person’s identity and that results in a sense of belonging. Bešić and Kerr’s (2009) study suggests that the importance of appearance differs from subculture to subculture. Hall (1997:2) notes that “in any culture, there is a great diversity of meanings” and therefore argues that the construction of identity marks difference. Bešić and Kerr (2009) argue that youths identify with subcultures known for being radical to cope with behavioural inhibition or shyness. It is suggested that youths do this to draw social boundaries and to relieve pressure or expectation to interact with unfamiliar peers (Bešić and Kerr, 2009). The other purpose suggested by Bešić and Kerr (2009) is to provide youths a self-handicap so if or when failure comes it is associated with the actions the youths do rather than their abilities.

Bešić and Kerr (2009) conducted a study that recruited youths from classrooms aged 10-18 years testing behavioural inhibition differences between Radical crowds like Punks or Goths and other crowds such as Nerds and Jocks. Questions were asked based on situations that mainly involved interaction with strangers and rated what their fear would be. Results demonstrated that radical groups such as Punks were significantly more inhibited than independents (those who do not identify with a peer crowd) and non-radical groups. This suggests that subcultures such as Punks use their appearance and identification with a Radical group as a coping mechanism for being shy and socially awkward.

According to Downes (2012) women used punk culture to transgress gender and sexual hegemony. It is argued that “women’s contribution to punk culture has been undermined in retrospective accounts…that focus on male performers” (Downes, 2012:204). Downes (2012:206) therefore argues that women “used punk culture to construct subversive critiques of middle-class heterosexual femininities and challenge sexism in British popular culture”. Punk subcultures were largely seen as male dominated and even subcultural studies main focus is largely on white, male subcultures. This is supported by McRobbie and Garber (1976) that the main focus of Subcultural studies is “whiteness and maleness” (Williams, 2007:581). Hodkinson (2007) further supports this point that McRobbie and Garber (1976) criticises Subcultural analysis “for focusing on largely outdoor spectacular subcultural activities…to have excluded a largely separate female youth culture” (Hodkinson, 2007:7). Downes (2012) notes that punk culture and music is not essentially male but is socially reproduced as masculine. As women used punk culture to challenge gendered expectations their transgression were policed by fears of violence and sexual assault (Downes, 2012). Double standards in Punk subculture according to Leblanc (1999) emerged as “punk girls had to negotiate their sexual activity in relation to being labelled a ‘slag’ or a ‘drag’; sexual exploits of punk men did not interfere with their punk status” (Downes, 2012:207).

Context and Composition

Hodkinson (2007) argues that youth subcultures form as a result of young people occupying a period of instability and transition. Adolescence according to Hodkinson (2007) is when “individuals break free from many features of childhood without yet fully adopting all of the characteristics associated with being an adult” (Hodkinson, 2007:2). This suggests that adolescence is a confusing period of transition from childhood to adulthood. According to Williams (2007) the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) believed that “British subcultures represented working class youths’ struggles to differentiate themselves both from their parents’ working class culture and the dominant bourgeoisie culture” (Williams, 2007: 575-6). This suggests that many youth subcultures in Britain were predominantly working class and according to Hodkinson (2007) excluded young women and ethnic minority youth.

O’Connor (2004) draws attention to the difficulties of identifying social and cultural capital with Punks, and divides the Punk culture into four groups: ‘art punk’, ‘major label successes, ‘political and DiY Bands’, and ‘youth anthem bands’. O’Connor (2004) suggests that overall punk culture is viewed as a working class, but argues that each category possesses different levels of social and economic capital based on Bourdieu’s model. O’Connor (2004) notes that art punks are more likely to be from middle to lower class backgrounds, but argues most Punk bands were successful and came from middle class backgrounds.

Cultural Symbols and Consumption

According to Williams (2007) subcultural expressions were most likely to appear in leisure spaces and style emerged as signifier of subcultures. Williams draws upon Cohen (1972) in the identification of four dimensions of style: dress, music, ritual, and argot or class. In relation to clothing, Williams (2007) draws upon the term bricolage from Clarke’s (1976) work, which is “the reordering and re-contextualisation of objects to communicate fresh meanings” (Williams, 2007:579). This means that objects that were encoded with a previous meaning are recoded into an object that signifies and represents that subculture. Williams (2007), notes that Punks sometimes have the swastika on a jacket or jeans to shock, as that symbol is commonly encoded as the symbol used by the Nazi’s in World War Two. These signs according to Hall, Hobson, Lowe and Willis (1980) are referred to ‘maps of meaning’ and they have a range of social meanings, practises and usages. This means that while some individuals may decode the symbol as signifying a particular item it may be decoded as something totally different in a subculture. Another signifier of punk subcultures is that of the punk hairstyle that Hebdige (1979:66) describes as “consisting of a petrified mane held in a state of vertical tension by means of Vaseline, lacquer or soap.”

Consumption of such products to create identity is essential to this subculture as appearance in punk is crucial as mentioned previously. Consumer culture according to Hebdige (1979:74) has had a major contribution from “the relative increase in the spending power of working class youth”. Consumption cannot take place however, according to Hall (1980) without meaning in a particular item: “if no ‘meaning’ is taken, there can be no ‘consumption’” (Hall et al., 1980:129).

Media Presence and Representation

As stated previously by Hebdige (1979) the appearances of Punk shocks individuals outside the subculture. Judging by headlines in newspapers such as the Daily Mirror describe individuals who identify as Punk as filthy, full of fury, evil and associated with drug abuse.

These language used by the media to represent punk subcultures is according to Hall (1979) is a process of the ‘construction of other’. Punk subcultures are portrayed at other by the media as they are portrayed as different in terms of style. From the media’s portrayal of Punk they are deemed as dirty and dangerous. The pictures from websites dedicated to Punk artists, portray a different representation of Punk subcultures than the media. This may be a sign of different meanings as mentioned by Hall (1979).

These pictures denote Punk artists performing which is a huge part of their subculture. These pictures do not represent the performers as dangerous and dirty like the newspaper articles describe them.

Conclusion

There are a wide range of subcultures that vary in terms of appearance and style. Punk subcultures have shown that appearance is essential for belonging in that subculture, and that the style is a substantial part of a Punk’s identity. The literature has shown that the purpose of Punk subcultures style is to shock and to avoid communication with outsiders to the subculture. Although the literature suggests Punk is a male dominated subculture, women have been able to use a Punk identity to challenge sexism and the heterosexual middle class assumption of women.Hodkinson (2007) has drawn on how subcultures have become more apparent since World War Two and that young people having an increased income are able to consume products to construct their identity. Hall (1979) has suggested this is a substantial part to their identity and having a sense of belonging in that subculture. The signs and signifiers that make up the Punk culture have seen to have a different meaning to those outside of the subculture. Hall (1979) interprets this as decoding the symbols differently and a range of different meanings are produced. The media representation of Punk subculture is that of a negative one and describes them as dirty and a danger to society. However the Punk’s portrayal of their subculture is that of centred on music for enjoyment and self expression.

Bibliography:

Bešić, N., Kerr, M. (2009) ‘Punks, Goths and other Eye-Catching Peer Crowds: Do They Fulfil a Function for Shy Youths?’, Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19(1), pp 113-121.

Downes, J. (2012) ‘The Expansion of Punk Rock: Riot Grrrl Challenges to Gender Power Relations in British Indie Music Subcultures, Women’s Studies, 41, pp 204-237, doi: 10.1080/00497878.2012.636572.

Google Images (2017) Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=newspapers+on+punk&espv=2&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjkyvzO79jSAhUFQZAKHaWBBSYQ_AUICSgC&biw=1366&bih=613#imgrc=_, (Accessed: 15 March 2017).

Hall, S. (1997) Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, London: Sage Publications.

Hall, S., Hobson, D., Lowe, A., Willis, P.(eds.) (1980) Culture, Media, Language, London: Hutchinson.

Hebdige, D. (1979) Subculture: The Meaning of Style, London: Routledge.

Hodkinson, P. (2007) ‘Youth Cultures: A Critical Outline of Key Debates’, in Hodkinson, P., Deicke, W. (eds.) , Youth Cultures: Scenes, Subcultures and Tribes, New York: Routledge, pp 1-23.

Mason. M. (2008) The Pirate’s Dilemma, London: Allen Lane.

Merton, K. (1938) ‘Social Structure and Anomie’, American Sociological Review, 3 (5), pp 672-682.

O’Connor, A. (2004) ‘The Sociology of Youth Subcultures’, Peace Review, 16(4, December), pp 409-414, doi: 10.1080/1040265042000318626.

Punktastic (2017) Galleries, Available at: http://www.punktastic.com/galleries/, (Accessed: 15 March 2017).

Williams, J P. (2007) ‘Youth-Subcultural Studies: Sociological Traditions and Core Concepts, Sociology Compass, 1 (2), pp 572-593, doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00043.x.

Needs some work- crucially a time frame – Punk has changed it’s meaning greatly over time- an example is the classic ‘ Mohican’ hair style- You never saw these until the ’80s when Punk was already a ‘retro’ style, having re-crossed the Atlantic to the West Coast Punk scene and come back again.Geography is also important- Punk had varied regional expression (and still does) – See http://www.northeastpunk.co.uk

as an EG. IMHO Ethnography and first person accounts also needed- Punk was a very self aware and literate movement with many punk musicians writing autobiography at the present- and a lot of Punks in their 60s and 70s (some still touring!) whose testimony could be used. I was at Sunderland 1976-79 and wrote my Communication Studies dissertation on Punk! (Nowhere near as well referenced as yours)

LikeLike

PS- I’d have looks at the debate about ‘Subculture versus Tribe’ (Maffesoli)

https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/The_Time_of_the_Tribes.html?id=CJx4wxkiTl4C

LikeLike

Good summary of the debate

Click to access 2959cd1d4ba912a352e2d300af0f376e70d4.pdf

LikeLike